Garrett throwing the discus

Robert S. Garrett 1897, Professor William Milligan Sloane, and the Olympic Revival

A century and a quarter after the revival of the Olympic Games, it may be surprising what a tenuous, if ultimately glorious, undertaking it was. Princeton University had a notable role in its success.

Professor Sloane

Baron Pierre de Coubertin of France, who conceived of the Olympics as an uplifting and peace-promoting international event, had a strong ally in his friend William Milligan Sloane, a professor of Latin and, later, history at Princeton (then still known as the College of New Jersey). In 1894, Sloane began functioning as a one-man American Olympic Committee and advisor to de Coubertin as the baron built the modern Olympics movement.

Soon to find glory -- and a profound life experience -- as a multiple medal winner and unofficial captain of the U.S. team was Robert S. Garrett, Class of 1897. He was the scion of a prosperous Baltimore family, whose Irish immigrant great-grandfather had founded a shipping and banking company in 1819. A versatile 6’2”, 185 lb. athlete, young Robert applied his prowess not only to track & field throwing and jumping events, but represented his class in cane wrestling during Cane Spree.

Except for Prof. Sloane, the University at large was underwhelmed at the prospect of students traveling mid-academic year to an Olympic revival in Athens. The Daily Princetonian editorialized in general support but warned of the “most deplorable” prospect of athletes losing condition for upcoming meets against Columbia and Yale during their long travels to Greece and back. At Sloane’s urging, the Administration allowed Garrett and others to go but required them to train for this non-scholastic competition off campus. Sloane secured use of the grounds of a local women’s school, whose headmistress lobbied him to have women included in future Olympics. (Women did compete in golf and tennis at the next games in 1900, although not until 1928 in track & field.)

Garrett planned to compete in his specialties of the shot put and the long and high jumps. And, as he later commented, he also decided to enter the discus throw “merely for the sake of competing in an event that belonged to antiquity.” Guided by one of the few surviving descriptions of the implement, Garrett had a town blacksmith make one. But it weighed 20 lbs., and even the strong and well-coordinated junior had little success launching it. Garrett gave up his dream of competing in a classical event – for the time being.

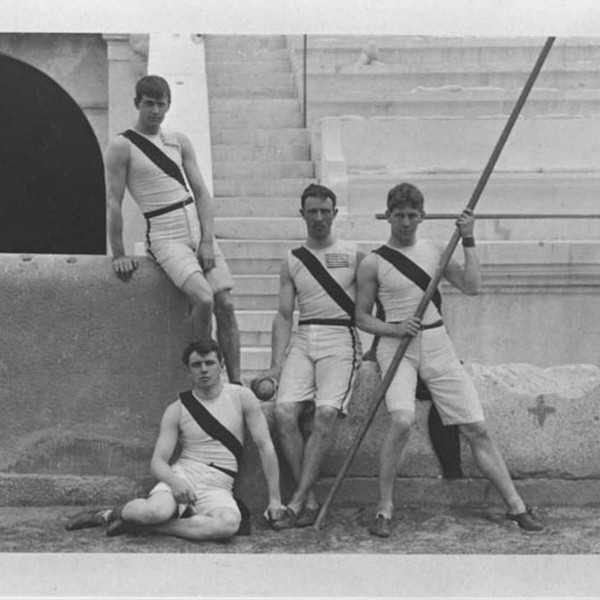

L. to R.: Lane, Jamison, Garrett, and Tyler

Such an odyssey would be as expensive as it was time consuming. But Robert’s mother understood the educational potential of the adventure. She underwrote the trip for her son and three Princeton track teammates. (His banking investment father had died in a boating accident when Robert was 12.)

To allow ample time to arrive in Athens comfortably ahead the competition’s announced start date of April 18, Garrett, his Princeton teammates and some other Americans sailed with Prof. Sloane on March 21 from New York bound for Naples. The rest of the U.S. team traveled separately. (Sloane soon made another significant journey, resigning later that year to accept a Columbia history professorship.)

But then, disaster loomed: Upon arrival in Italy, the Americans were made aware that Greece was still on the old Julian calendar. By Gregorian calendar reckoning, the Olympics were commencing on April 6, a mere few days – and a daunting distance -- away. A desperate travel sprint brought them to their journey’s finish line only the day before the games’ start.

Stretching his legs that night with a walk around the competition site, Garrett had a fortuitous meeting with a local man. He learned that the competition discus weighed only 2 kg. (4.4 lbs.), much lighter and smaller than his blacksmith-forged monstrosity. The Greek also generously gave Garrett some pointers on throwing the platter. Robert decided to enter the discus competition after all.

Garrett putting the shot

In the shot put, Garrett threw below his usual, managing to secure first place by a scant three quarters of an inch. But Robert shone dramatically in the discus. After two clumsy efforts, his final attempt sailed beyond the mark of Greece’s discus champion by seven inches. Teammate Albert C. Tyler 1897 was cabling dispatches back to The Alumni Princetonian newspaper (which featured a cover story on the Olympics with Garrett’s picture prominent in its April 16, 1896, issue. He reported that the other competitors sportingly celebrated Garrett’s surprise victory but the applause of the Greek contingent “was decidedly feeble.”

Garrett posted a second place in the long jump and tied for second in the high jump. Tyler was second in the pole vault; Herbert Jamison 1897 second in the 400 meter race; and Francis Lane 1897 second in the 100 meter sprint. With approximately 245 athletes from 14 countries (there is some question among scholars about the precise numbers), including 14 from the United States, the revived Olympics triumphed over earlier skepticism and were rightly hailed as a grand success.

Gold, silver and bronze medals were not awarded until the 1904 St. Louis games. But first and second place finishers in 1896 received, respectively, silver and bronze medals. Laurel branches – the classical Greek symbol of honor and victory -- were also given. Albert Tyler had the foresight to preserve his via impregnation with paraffin. Donated to Princeton by his widow, it was one of the very few mementos to survive the devastating gymnasium fire of 1944.

Garrett served as a Princeton trustee from 1905 to 1946. In 1948, Garrett – by then a prosperous 73-year-old investment banker and Baltimore civic leader -- donated his Olympic discus to the University. It also survived, with both relics now cherished links to the University’s vital and successful role in this landmark world sports event.

(There is some indication that the discus throw was added as a field event at Princeton in the years shortly after Garrett’s 1896 victory. More research needs to be done, with the potential of documenting this as yet another instance of Princeton’s innovative role in 19th and early 20th century American sports development.)

Under Garrett’s leadership, Robert Garrett & Sons, the mercantile and banking company founded by his grandfather in 1840, was listed on the New York Stock Exchange in January 1947.

Although his grandfather had supported the Union during the Civil War and Robert himself was a notable progressive in expanding recreational opportunities for Baltimore citizens, both privately and as the first chairman of the Board of Park Commissions he personally opposed racial integration of the city’s public parks, playgrounds, pools and tennis courts. In the 1950s, a majority of the commissioners voted for facility integration, and Garrett was asked to resign from the board.

When Robert S. Garrett died on April 25, 1961, he merited a New York Times obituary. Interestingly, the Times headlined his generous gift to Princeton of his superb collection of “Arabic” (Islamic) manuscripts (part of his magnificent overall medieval and Renaissance holdings).

Both Garrett and William Milligan Sloane were remembered during the centennial Olympic games. When the Olympic torch wended its way to Atlanta in early June 1996, it made an appropriate stop in the Princeton town cemetery for a commemoration at Prof. Sloane’s tomb.

And Kodak wished to use an image of Garrett in discus-throwing pose in a television commercial, with Champion requesting its use for a T-shirt. Both companies offered generous payment. This posed a dilemma for the descendants of a man who had been dedicated to amateurism in sports.

The Garrett family accepted the royalties, but then immediately donated the money toward construction of a new track & field facility between the University stadium and Jadwin gymnasium in memory of Robert S. Garrett 1897 – a gift now noted for all time on the donor board.

-Richard D. Smith, Princeton-area journalist/author, former University administrative staffer, and member of the Princetoniana Committee

Princeton's first Olympic heroes