Professor Magie

Physics professor William Francis Magie, who was dean of the faculty from 1912-1925, held anti-suffrage meetings at his home. The faculty, it was said, attended “in a body.” Magie didn’t mince words. “If we allow women to vote, we consent to the most profound political revolution that any free country has ever experienced.” The benefits of such a revolution, he continued, are “not worth a thought.” Transferring women from her position as “helpmeet and companion of men” to a position of social and political independence would be an “injury” to society.1

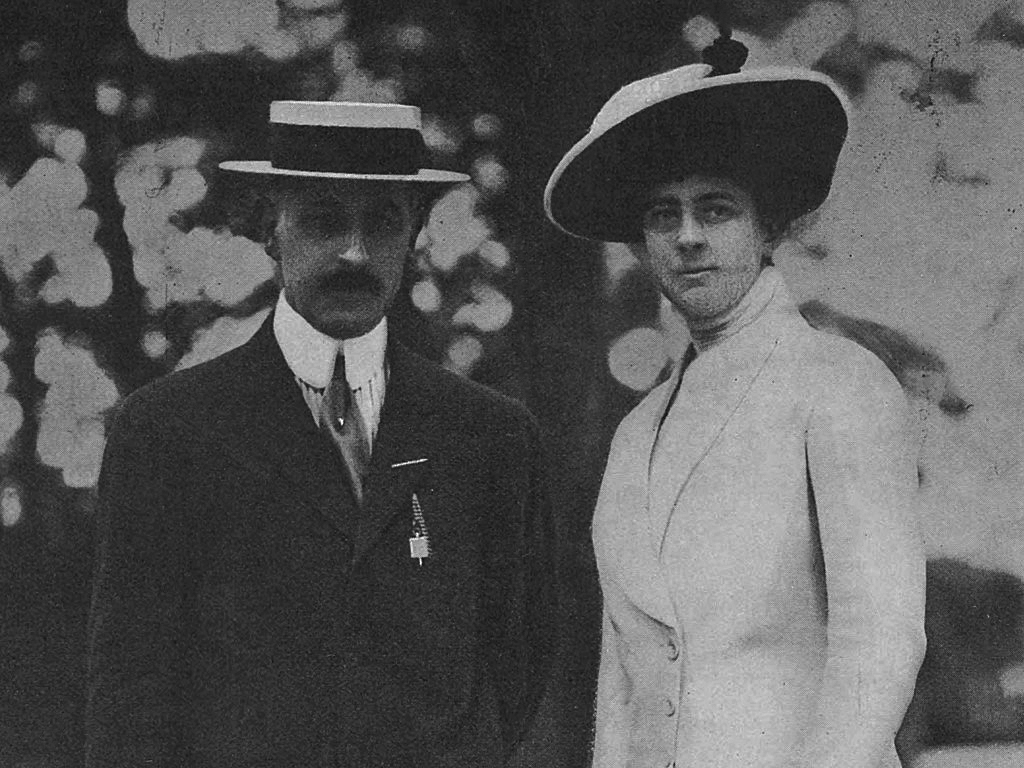

Preston and Cleveland

From 1913 onward, Frances Folsom Cleveland, the widow of President Grover Cleveland who was newly married to archeology professor Thomas J. Preston, joined Magie in heading up Princeton’s anti-suffrage campaign.

But suffrage sentiment was hardly unanimous across Princeton households.

Warren

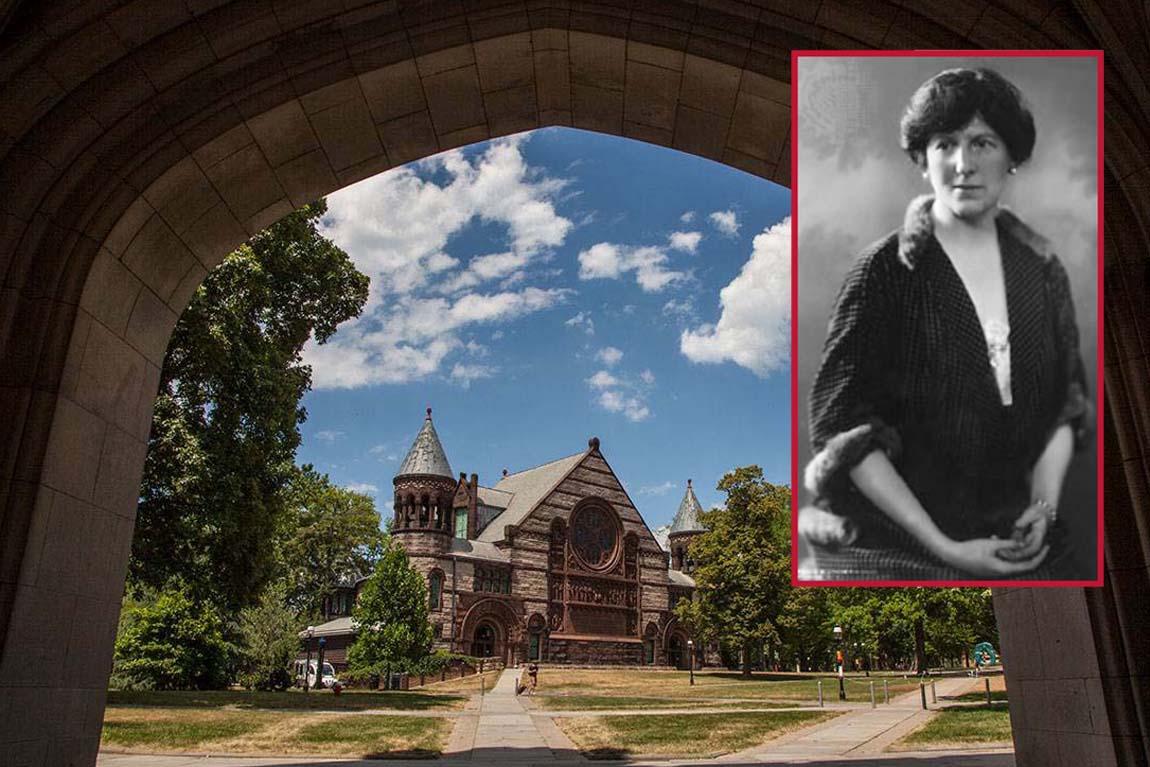

133 Library Place

Catherine Warren, the wife of Howard C. Warren, a professor of experimental psychology, spoke boldly for woman suffrage, no matter what it meant for her husband’s career. “Personally, I think suffrage is only one phase of a broader life for women,” she said.2 The Warren home at 133 Library Place still stands today.

Edith R. McComas, the wife of assistant psychology professor Henry Clay McComas, was a prominent suffrage leader, holding several offices for the Princeton Suffrage Committee. In 1915, she listed 72 founding members of the committee, including the wives of 18 professors.3

Still, the very public positions that faculty wives took on suffrage gave rise to a persistent rumor that any Princeton professor whose wife advocated for the cause would be fired. Eventually, University President John Grier Hibben felt it necessary to refute the rumor.

“We have always prided ourselves at Princeton upon our immemorial tradition of tolerance and open-mindedness,” he said. “Our professors, their wives, and all connected with the University, have complete liberty of thought and of the expressions of the same.” 4

Wilson arrives in Princeton in 1915

However, in 1915, the antis in Princeton scored a major victory when the town’s voters defeated a state-wide referendum that would have granted women in New Jersey the right to vote. Princeton’s vote was 502 in favor of the amendment and 684 against. President Wilson had returned to the state to cast his vote, as he had been president of Princeton University and governor of the state and still had a home in Princeton. He had been dragging his feet on the suffrage question, never taking a public position, so it was surprising that he voted in favor of woman suffrage. But he qualified his position saying that he was voting as a private citizen and not as president. His vote implied that instead of favoring a constitutional amendment, he wanted states to be able to decide individually whether women could vote.

Not only was Wilson’s suffrage endorsement not enough to convince his home district, but across the state, the referendum was defeated by about 50,000 votes. The only county to pass the referendum was Ocean County, perhaps because of its large Quaker population. Quakers believe in the equality of the sexes, and women in Quaker communities had long had educational and societal leadership opportunities not afforded other women at the time.

During the 1915 campaign, Alice Duer Miller, a well-known poet and author, was invited to speak in Princeton. The meeting was held in Alexander Hall on the campus. The title of her satirical talk was, “Are Women People?” In 1868, the 14th Amendment to the Constitution granted rights to “persons” who were citizens of the United States, but the courts ruled many times afterward that these rights didn’t apply to women. Suffragists had to argue that women were people!

"Are Women People?"

1 Newark Evening Star, October 4, 1915, p. 6.

2 “By Mrs. C.C. Warren,” Newark Star-Eagle, September 14, 1914, p. 16.

3 “Woman Suffrage Sentiment Is Rapidly Growing in Princeton, With Two to One Percentage,” Trenton Evening Times, July 6, 1915, p. 12.

4 "Princeton Not Against Cause of Suffrage," Newark Star-Ledger, June 30, 1914, p. 1.