The Crime Scene

The following exhibit is based on an article written by S. Aaron Laden '70, published in his 50th Reunion Class Book. It has been adapted and augmented for use by the museum.

Tom Swift '76

Chief Curator

**The Notorious Cornwallis Cannon Theft of 1969**

The germ of the cannon hoax was born on a warm spring evening in 1968. In an upstairs room in Holder Hall, we talked of the legend of the Cornwallis cannon, the thousand pound gun buried muzzle-down outside Whig Hall, abandoned by Lord Charles Cornwallis after the battle of Princeton in January 1777. It later showed up at New Brunswick in the War of 1812 and became the subject of the nineteenth century “cannon war” between Princeton and Rutgers, in which the cannon was stolen and re-stolen repeatedly over a period of decades. After one theft by Rutgers students, Princeton students retaliated by stealing a musket collection from Rutgers. A peace negotiated between Princeton and Rutgers presidents culminated in the first intercollegiate football game in 1869.

I remarked, “wouldn’t it be terrific if we could steal the cannon, making it appear to be the work of Rutgers students? Couldn’t you just see Princetonians swarming New Brunswick, pillaging everything not nailed down? Then, we could bring back the cannon ourselves as conquering heroes.”

But as everyone familiar with the cannon story knew, the cannon couldn’t be stolen because the last time it was stolen and returned to Princeton, it had been sunk in a massive subterranean base of cement. My host, a member of the Orange Key Society, then commented that there was a little-known fact about the cannon that would interest me. It had been unearthed a few years earlier, and the cement was chipped away in order to study inscriptions on the barrel. It had been replanted without the cement.

There was another antecedent to the cannon caper during the very first week on campus for the class of 1970. In September 1966, in a crowded dormitory room in Blair Hall, I sat on the floor with a breathless clutch of fellow freshmen listening to H. Walter Dodwell, Director of Security, tell of many past incidents of aberrant student conduct . I clung to every word and came away convinced, as Mr. Dodwell intended, that one misstep violation of parietals, of the Honor Code, or of other sundry rules and regulations, and I would be expelled, the dream of attending Princeton extinguished for life.

Time passed, however; it was September 1969. A lot was happening. Plans were underway for the “Moratorium against the Vietnam war” to be held in October and a march on Washington in November. It was the first month of coeducation at Princeton after 223 years of male monasticism.

Publicity about the one-hundredth anniversary of the first intercollegiate football game was building. The game would be televised nationwide. It was a turning point for the Princeton football program that had just abandoned the single-wing attack for the T-formation. Rutgers had decided to turn professional, and the Princeton-Rutgers series was soon to end. This was clearly the one historic moment to steal the cannon. I felt that it was my responsibility to do so.

I was, insofar as I knew, the only scholar at work on this problem, and I was in possession of valuable and little-known information, the fact that the cannon was not embedded in cement, a fact that made the entire project possible. The idea had lain dormant for eighteen months, but the intellectual framework had been established, and time was short. I mulled over the logistics – how to get a truck, how to disguise the truck as an official vehicle, how to finance the project. What about tools? What about manpower? Would students even be interested with so much else going on?

Then came a sudden blinding flash of insight - the solution was not to steal anything at all, but to create the illusion of a theft by digging a hole and piling the removed earth onto the exposed butt of the cannon. The cannon would disappear and in its place would be a gaping pit. The scene would be defined by painting a few incriminating slogans in Rutgers red.

To find out what was wrong with this plan, I ran next door to sound out my friend and confidant, Ed Labowitz ‘70. Ed and I then bounded up the stairs to Brian Hays ‘70’s room. We drew up a list of nine other potential conspirators to invite into the project.

The meeting was held in my room at 23 North Edwards Hall the following night. A member of ROTC, Ed wore his military uniform. Having worked part-time during high school in an Army-Navy surplus store, I wore an army field jacket and black leather boots. Brian donned his U.S. Marine Corps utilities.

I had prepared an easel bearing a large drawing of the battle plan showing the south elevation of Nassau Hall, Cannon Green, the road along the south border of Cannon Green, and the west side of Whig Hall with the butt of the Cornwallis cannon protruding above ground level.

Not knowing the nature of the project, nine curious young men joined us, in my room. Oddly, although we had invited nine people and nine people came to the meeting, they were not exactly the same nine we had invited. Nevertheless, we had a stalwart crew, and the meeting got underway. I outlined the familiar history of the cannon and emphasized the significance of this special moment in time before the Rutgers game that was to commemorate one hundred years of college football. Then, turning to the drawings, I discussed the physical setting. Finally, in my most dramatic style, I drew a hole next to the cannon, saying, “we will dig a hole here,” and drawing a heap of dirt over the top of the cannon, “and pile the dirt here!” The room erupted in unanimous and enthusiastic acceptance of the project.

The team was possibly the very best crew that could have been assembled on short notice for the purpose of digging a hole and making the world stand up and take notice. Labowitz knew a young geology department graduate student named Denis Roy who willingly lent us shovels and picks without insisting on knowing for what purpose. The muscular and athletic members of the group, including Brian Hays ’70, Rich Weikel ’70, Rich Stafford ’70, Ken Homa ’70, Jim McElyea ’70, Peter McLaughlin ’71, and Greg Hand ’73, chose to do the actual digging. Labowitz, Laden, Luis Hernandez ’70, Jim Anderson ’70, and Dale Stulz ’73 were to be sentries.

Early on Wednesday night, September 24, we began monitoring the scene. Greg Hand and Dale Stulz lived on the second floor at the northeast corner of Edwards Hall with a commanding view of McCosh Walk and Whig and Clio Halls. Others monitored the comings and goings of security personnel. We watched and waited until all was quiet, and we began patrolling on foot.

But wait! What’s this? We saw three or four black-clad figures slinking from tree to tree on Cannon Green. Who were these cartoon-like characters and what were they up to? As we approached, they froze.

“Are you trying to steal the clapper?” Labowitz queried.

“The what???”

We then gently explained that, though we would not personally wish to harm them, we could instantly rouse dozens of angry men from that dormitory right there and have them thrashed. The impasse was broken when Dale Stulz, a freshman in his first month on campus, suddenly yelled, “Come on, boys! Let’s get ‘em!”1 The intruders immediately turned in a panic and fled, with us half-heartedly following for a dozen yards just be sure we were rid of them. Thanks to Dale’s quick response, we were able to preserve the calm necessary to pursue our objective without detection.

We found, however, that the intruders had painted the big cannon red and placed a four-inch round red cardboard disc decorated with a red raiders decal on the butt end of the cannon. More useful to us, they had also painted a few big red “R’s” on the trunks of elm trees. Since I happened to have a can of black spray paint in my dorm, it was a simple matter to repaint the big cannon black.

Well after two o’clock, the campus was silent, and the sentries took their posts. Out came the picks and shovels, and the muscles went to work. On a few occasions, pedestrians ambled by, and the sentries sounded the alarm. Digging ceased until the danger passed. Luis Hernandez recalled, “at one point a uniformed guard, not a proctor, did walk by. The alert system worked and everyone found a place to hide.”2 Brian Hays wrote, “Another amusing event during the actual dig was due to a slight break-down in surveillance. During the dig, a sleepy student walked by on the way home from the library, looked at us, and just kept going. We were too busy and too deep into the project to do anything about it, so while he kept walking, we kept digging.” 3

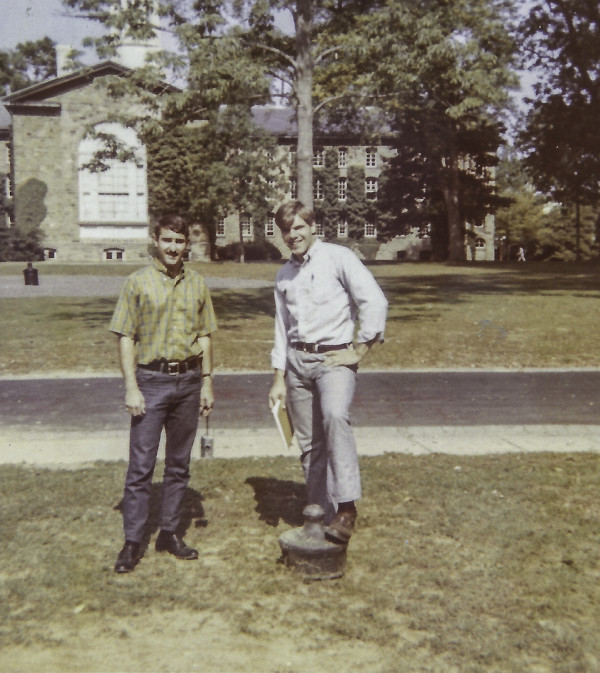

The diggers at work

Implicating Rutgers

The digging actually went rather quickly, despite the fact that only one digger could fit in the hole at a time. I took the opportunity to spray a message in red paint on the asphalt roadway (where it would cause no lasting damage), “Thanks, love Rutgers ’72.” Brian Hays recalls that the diggers embellished the scene by using shovelfuls of dirt to create “drag marks” in the grass leading to the road.4 Jim Anderson took some photographs in the dark to document the project.

The job having been completed without discovery, we repaired to Edwards for a celebratory cold beer.

L to R front: Richard Stafford ’70, Richard Weikel ’70, Edward Labowitz ’70, Luis Hernandez ’70. L to R back: James McElyea ’70, Aaron Laden ’70, Dale Stulz ’73, Greg Hand ’73, Peter McLaughlin ’71, Brian Hays ’70. Not pictured: Ken Homa ’70 and Jim Anderson ’70

So far, it had been a simple matter of digging a hole. Once accomplished, things became more interesting. Our group of conspirators was more special than I had first realized. Among our number were Ken Homa and Jim McElyea, ad manager and business manager of the Daily Princetonian, respectively. Ed Labowitz was a news and sports reporter for WPRB, and Jim Anderson was a Press Club member and stringer for national wire services. One of our group happened to have the phone number of Elliott Greenspan, editor of the Rutgers Targum. Under the influence of our success and the beer, we decided to give Mr. Greenspan a call – at maybe five o’clock in the morning. We informed him that the cannon had been stolen. Greenspan wasn’t prepared for this news, and indeed, he may not have had any idea that there even was a cannon to steal. But the information served as a wake-up call, so to speak.

At six o’clock on Thursday morning, Ed Labowitz went to the security office in Stanhope Hall. In Ed’s words:

I [Labowitz] went up to the U Police and told them I was supposed to do the 7 AM news on WPRB. […] I said someone had called me from Rutgers, advising me that he had masterminded the theft of the cannon. I told the officer that, sure enough, the cannon was gone. To my amazement, the officer said, “Oh, no. We got a call in the middle of the night from some Rutgers students that they had painted the cannon red, but we went out there and it’s black.” I asked the officer if he realized that there were two cannon out there.

He didn’t.

I said, “Well, one is black, and it is in the center of Cannon Green. It is still there. The other […] was next to Whig Hall, but it’s gone.”

I went to WPRB and read over the air a news story I had written about the theft. I called the Rutgers station, they recorded my story, and used it all day long on their newscasts. 5

Thursday afternoon and Friday morning papers throughout the country reported the theft of the Princeton cannon by Rutgers students.

Later on Thursday, in Labowitz’ account:

Then the head of our security [H. Walter Dodwell] was interviewed by “real” reporters and expressed his amazement that the 2000 pound cannon could have been taken. He had thought that it was embedded in concrete and, thus, was surprised to see there were no concrete fragments in the dirt which the Rutgers students left … behind. He called the action of the Rutgers students, “A Masterful Coup.” 6

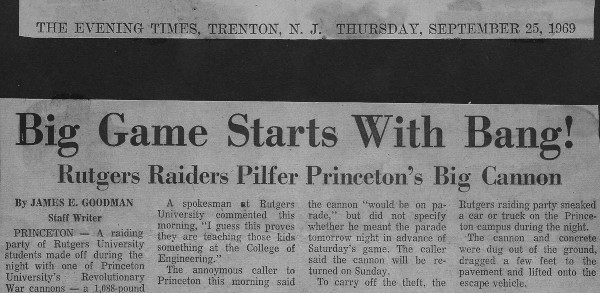

Reported in Trenton

The story spreads

The Evening Times (Trenton) also reported Dodwell’s remark and added that Dodwell “is cooperating with Rutgers officials in an attempt to prevent retaliation by Princeton students against the Rutgers cannon in front of Old Queens.”

The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin announced, “The Princeton-Rutgers ‘Cannon war’ is on again. In a pre-dawn raid on the Princeton campus this morning, a group calling themselves ‘Rutgers Sophomores’ made off with a 1,000-pound Revolutionary War cannon.”

As Jim Anderson wrote at the time of our forty-fifth reunion,

I [Anderson] was a member of the Press Club, which consisted of 8 students who were Princeton correspondents for the various newspapers that were interested in events on campus, such as the ”Trenton Times,” “Philadelphia Inquirer,” and “Newark Star-Ledger.”

After our celebration that night in Aaron’s and Ed’s dorm suite, I went to sleep and was still asleep when my roommate, John Spencer, woke me up to tell me there was a phone call from Jeff Greif, a fellow Press Club member. Jeff told me how the cannon had been stolen and how I should get down to the office so as to send in my story to my newspaper, the “Philadelphia Inquirer.” It surprised me how the story in a sense wrote itself. I didn’t have to deceive my fellow newspaper reporters. Jeff wrote up the information that the others used in writing their individual stories.

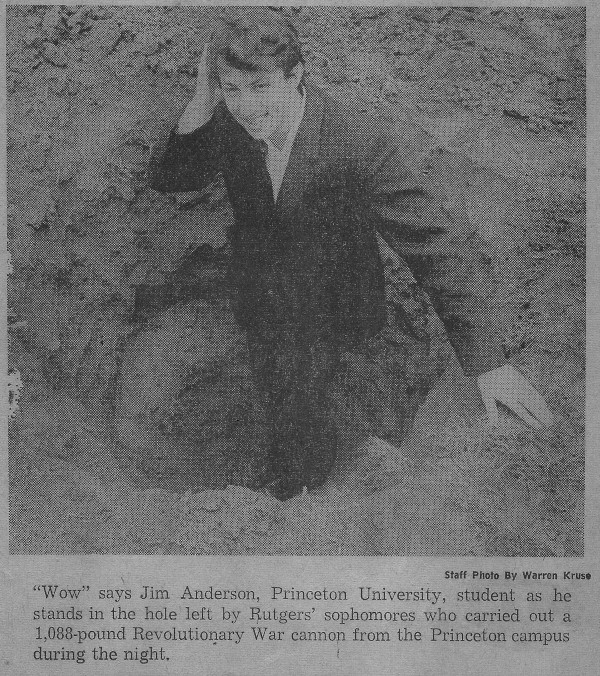

Anderson in the hole

A couple times during the day I wandered over to the scene of the crime. Just by chance, there was a photographer there. He asked me whether I’d step down into the hole where, supposedly, the cannon had been for a photo in which I would look bewildered. I thought that to do so was a great irony, as I knew exactly what had happened. That photo was picked up by United Press International and published in many newspapers around the country, including my hometown paper, the “Cleveland Press.” 7

The time for decision had arrived. I was perhaps the only one who wished to allow the hoax to continue without further intervention on our part. The rain would eventually wash the dirt away or the grounds crew would fill the hole, and everyone would realize that they had been duped. Others among the group thought otherwise. There were those who were concerned that the football team would be demoralized and perhaps lose the game. Still others were loyal to their commitments to publish the truth in the Daily Princetonian in the Friday morning edition. As Ken Homa wrote,

On Thursday evening (September 25) the group reconvened in Aaron’s room to debrief and have a few beers. There was much shared pride and a bit of concern that the stakes were getting high since university administrators - notably, security chief Dodwell – were saying some pretty wild stuff to the press. So it was decided to leak the story to a couple of friendly media outlets. 8

The Prince breaks the story

That night, Ken was “dispatched to do a grand reveal to his reporter contacts at the Daily Princetonian,”9 and on Friday morning, the Prince published the scoop with a splashy banner headline, “Cannon caper giant hoax: Look for it under the dirt!” followed by a major story attributable to “a spokesman for the group, all of whom requested to remain anonymous.”

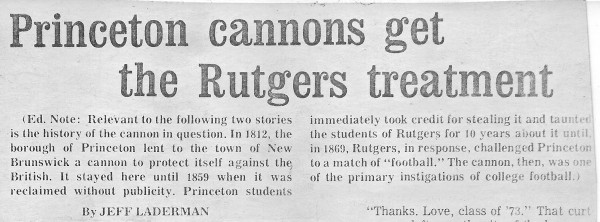

Rutgers takes credit

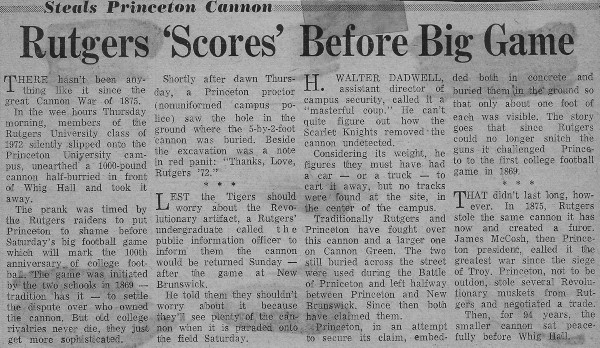

Philly Inquirer

By Friday afternoon, September 26, the news of the theft was nationwide, but only the Princetonian had published the true story. All of the other papers reported the cannon stolen. The Rutgers Targum headline intoned, “Princeton Cannons get the Rutgers treatment.” The Philadelphia Inquirer boldly reported, “Rutgers ‘Scores’ Before Big Game.”

Some of us on Thursday and Friday periodically walked past the scene of the hoax to observe the student reaction. No one questioned the idea that the cannon was gone. Around mid-day on Friday – after the Princetonian story – groundskeepers arrived to restore the cannon and fill the hole. Labowitz wrote, “several of us went out and saw the grounds crew filling the hole. Nearby stood President Goheen, smiling ear to ear.” 10

A television news team from WABC New York came to the campus to film an interview. Thrust forward as the spokesperson for the “Centennial Dozen,” I muttered something about our motive to “restore the hoax as an art form.” The expression came out better than expected - and stuck, as emblematic of the event.

SI gets it really wrong

Cannon restored

A week later, the story reached the weekly roundup of college football in Sports Illustrated, but they had some difficulty with the replay, reporting, “On Wednesday night 12 Princeton undergraduates removed the Little Cannon originally fired by George Washington’s underdog team at the Battle of Princeton from its concrete base on the campus and buried it three feet away.”

The January 19, 2011 issue of the Princeton Alumni Weekly carried an article by Gregg Lange ’70 ranking the “very best of student escapades". The cannon hoax was ranked number two after the great train robbery.

Strictly speaking, the cannon theft was a hoax, not a prank – not like leading a horse up a flight of stairs. It was not a fraud – unlike the Oznot affair in which students falsely created an academic record and recommendations to admit a nonexistent student (Okay, there was an element of fraud in the way we publicized it.).

Nor was it a crime – like waylaying a train and waving guns in the passengers’ noses. It wasn’t even vandalism – we put red paint only on the asphalt roadway where there would be no damage. The Rutgers intruders aided our cause by painting on the trees – something we never would have done.

No, ours was a hoax, done for the sheer beauty of the thing. The essential element was to set the scene – a hole in the ground where a cannon was known to reside and a little red paint, done at the perfect historical moment. The performance art was not what we did, but how the community reacted. Everyone leaped to his own preconceived conclusion. Campus observers concluded that the cannon had been stolen - and by Rutgers students. Dodwell concluded that a truck had been driven onto the campus. The Rutgers Targum decided that the cannon was in New Brunswick and would be paraded at the game. As reported on September 25, 1969 by the Trenton Evening Times, “A spokesman at Rutgers University commented this morning, ‘I guess this proves they are teaching those kids something at the College of Engineering.'"

So what does this all mean fifty years later? The university, the nation, and the world have radically changed. The Princeton-Rutgers football rivalry is dead. After half a century, I am pleased to think that I may have had greater accomplishments in my life than my role in the hoax, but the Princeton-Rutgers Cannon Hoax of 1969 has clearly been my most productive action in terms of enjoyment per unit of effort. I have heard from many others in our group that they, too, have derived joy year after year from having been part of Princeton lore and having been recognized in our senior class poll as the “Best Move of the Year.”11

Tenth Reunion in 1980

2022

Some of my fellow hoaxers have stated it best. Ken Homa wrote: a “couple of weeks ago I was walking the campus with a couple of my young grandkids. I told them the story of the hoax. Almost fifty years after-the-fact, that story still resonates with young and old.”12 As Brian Hays wrote, “It’s a privilege to be a part of such a disreputable group.”13

Notes:

1Hays, Brian: personal communication by email, Feb. 16, 2018.

2Hernandez, Luis: personal communication by email, Feb. 7, 2018.

3Hays, op. cit.

4Hays, ibid.

5Labowitz, Edward S: unpublished manuscript, 2002.

6Labowitz, ibid.

7Anderson, James W: personal communication by email, May 26, 2015.

8Homa, Ken: personal communication by email, February 9, 2018.

9Homa, ibid.

10Labowitz, op. cit.

11Taylor, Ralph A. (Ed.), The 1970 Nassau Herald, 1970, p.423.

12 Homa, op.cit.

13 Hays, op.cit.